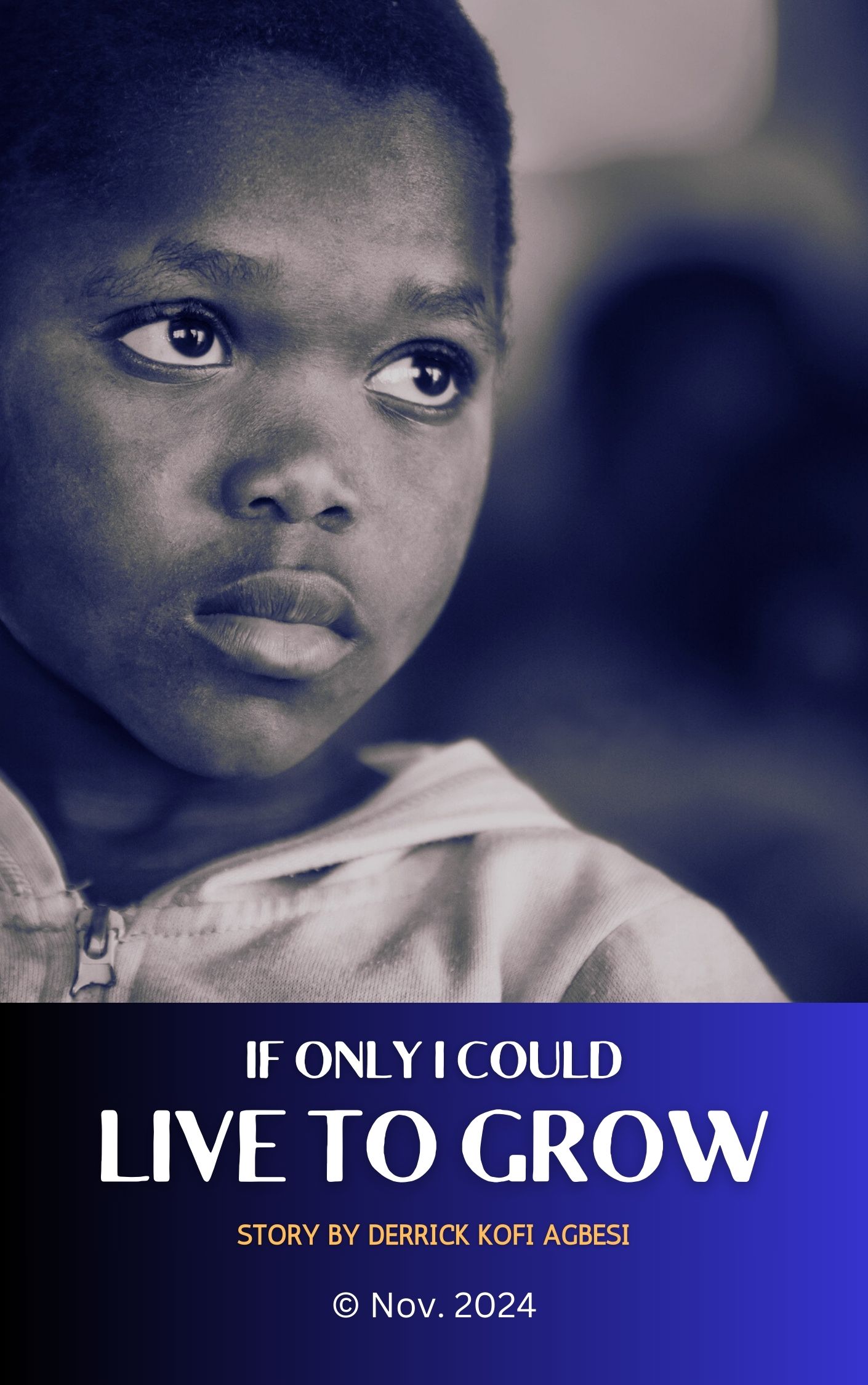

IF ONLY I COULD LIVE TO GROW

Derrick Kofi Agbesi@derrickkofiagbesi886981

1 year ago

Chapter 1

My dad was light-skinned, tall, had thick hair, a bold face and a natural hefty physique. Mum was chocolate, and had a comely nature but was neither tall nor short. Dad was outspoken and would punish you once and heavily for one offence. Mum on the other hand was reserved and would punish you mildly but severally for just a single offence. I dreaded the latter punishment more because I felt it summed up and even went beyond a double of the former. As a result, I feared mum more.

I picked most of dad’s traits but mum’s complexion only. However, both would tell me they could trace my character from my stubborn grandfather, mum’s dad. Well, I was indifferent to any description levelled at me as a child. And as a child, I grew to love food than anything else. Put a ten-cedi note here and a one-cedi food there and I would trample on the note and run for the food thinking the cedi note never existed let alone considering its tenfold value. Thus, I was only concerned about my parents feeding me well enough so I wouldn’t go about begging for food.

Dad and mum also believed in God but hardly went to church. The same dad and mum reckoned that sending me to church would tame the spirit of stubbornness in me but I never understood why they felt I was such. And church services sometimes were good. I cherished the ones that came when the year was about to end. They called it Christmas services and I had no idea why they gave it that name. For all I knew and valued and never missed, children of my age were given candies and I liked candies for their super sweetness. Thanks to sweet Jesus. The dances in those cute suits and starchy shoes too were lovely memories. One could go high on the Christian music, thoroughly forgetting that the track had ended and drummer and everybody had gone home. One was still there dancing and mum came down to the church, too surprised to see her son there alone doing those rigid moves. She couldn’t contain herself and as a result, lashed the hell out of him.

Chapter 2

Dad and mum too never underestimated their culture. They believed that culture brings love and togetherness. The Tedudu Festival was two days away and that we had to be snappy to harvest those yams. The school, Asogli D/A Primary School of which I was one of its pioneer pupils, was on vacation and as a pupil, the only way the holiday wasn’t wasted in causing troubles in the neighborhood and therefore saving me from the spankings was by following dad to the farm. Apparently, that was the only cure because

on the farm, dad was there, his hard gaze was there and these were just sufficient to put me in place and be a good boy for once. And as a good boy when dad said don’t touch this, you as the child saw the whole thing as law and you had to obey. But at the same time, something told you to take a few steps and touch what was there, but in the end, you knew dad meant you shouldn’t touch anything at all, unless he had instructed you to. And that was something I grew never to understand and my inquisitiveness to having a feel and taste of anything I laid my eyes on mostly landed me in trouble - either a fight here, a beating there or a hot chase in between. The lattermost experience had somehow prepared me for the junior athletics championship. The competition was scheduled on Friday and my school was to contend with other schools in the same district. All set, the starter pistol fired and the claps followed: “Edudzi, run!”, “Edudzi, run!”, “Edudzi, run!” and the Edudzi in me had been promised some meat and he didn’t want to miss it. How could he miss a whole fried grasscutter? He kept on running, sprinted past the leading lanky guy and broke the dead heat and kept on running like a lunatic even after crossing the finish line. “It’s okay, stop! You’ve won!”, the fans attacked me amidst the applause. I was merely enjoying myself and little did I know the relevance of the outcome if I kept the lead to the end. Oh well, I must say winning the brass medal was something I never gave much thought to but I was glad I won something for my school for the first time. Edudzi, Victory. Indeed, with my long legs and my unsatiable desire for my ‘trophy’ meat, I pressed on and became victorious. But I had been waiting uneasily for this fried grasscutter for hours, for days, for weeks and it never came. I don’t know but later a teammate told me our coach and class teacher, Teacher Agbovi had an eye on my ‘trophy’ meat, took it home and supplemented it with a pepper soup. “Oh why?!”, I cried. “Indeed, Teacher Agbovi has caused me much pain.”… And the next day after the game, I never understood why a whole Teacher Agbovi while teaching Maths was complaining more and more about visiting the toilet. Nevertheless, I was gratified seeing my two special people, mum and dad happy. And I must say the beans stew that came as their reward was nice and in the darkness I hid and ate it alone and I thanked God when He was creating man, He never forgot to attach the mouth and the stomach.

Chapter 3

Dad was adept at farming and earned all praise and respect from the village folks. Following him to the farm as his son on Saturdays became a routine and I would say it gladdened me because it granted me a firm guarantee to flee from household duties. Washing hundreds of dirty utensils was one thing I hated most but I dared not tell anyone especially them. I mean dad and mum and that would be simply sound like dictating to them. I would rather prefer dusting the trays, anyway.

Dad’s farm was a few metres away from the village and was a twenty-plot of land, a reward handed down to him by the chief on grounds of his hard work and sincerity. I have vivid memories of how he dealt with those giant weeds on his two-acre beans farm just in one day.

The next morning was Saturday. The Tedudu Festival was going to be the next day and I realized the celebration always fell within the late days of the 8th month, or the early days of the 9th month, or a period in between. In one of my mum’s ancient stories by the hearth, I recall her telling me, we the tribes of our Asogli State celebrate the Tedudu Festival to honor one of our ancestral hunters. According to the story, he discovered a yam tuber in the forest during his hunting expedition when severe famine had struck our Asogli State. He cooked and ate part of the tuber, then hid the rest in the soil. He later decided to go for it and to his surprise, it germinated and grew bigger, saving the entire Asogli State from hunger. In gratitude, the period is observed every year to thank the torgbewo and mamawo, our ancestors and the gods, for a bountiful harvest, and to offer prayers to Mawuga for good health and prosperity. Despite not fully grasping the significance of the festival or its timing, I was always thrilled whenever it drew near. For as long as I could remember, even if our home had gone without food for months, there was always a glimmer of hope that two or three yam tubers would find their way into our household for the celebration, and that’s what mattered.

The morning sun had set in earlier than expected. Our youngest sibling, Little Adjo had to stay home with mum for the routine household chores while as usual, I was to accompany dad to the farm but this time around to help him harvest some yams he planted the last season.

It was a few minutes to six and I was told to fetch the cutlass and hoe in the shack, which I did. The akple and fetri detsi and the small gallon of drinkable water most of the time were brought later to the farm by mum, especially when we were getting late. I could forget the cutlass and hoe but never the catapult because David in the Bible was my hero. I chose David as my hero because our Sunday school madam once taught us that David, a diminutive youth, slayed a giant called Goliath with a mere catapult, and that if a mere catapult was that powerful to kill a whole giant, why don’t I take it along for defense against any wild attack against us on the farmland? I badly needed farm cloth too and dad gave me one of his own: something too big and might have aged thrice my age. But on the farm, no one fancied nor cared how well you dressed and that was no struggle.

“Whew! Whew! Edudzi, off we go now!”, dad registered. We strode through narrow farm paths. It was a rainy season and most of the farms had come up with good produce: fresh pineapples, grains, legumes, cassava, yam, edible leaves… the epitome of gracious green and decent brown -- the unmatched taste and colour of the earth! With my catapult loaded with pebbles, I never spared any talkative bird, any rat, any grasscutter or any bush animal that crossed our path or spotted from a distance. I hated the birds most because I felt they made too much noise and too much noise from such nagging creatures irritated me so much for two primary reasons: one, that they have no respect for man and two, that they feel they have more dominion over the farms than man and that they can choose to make unnecessary noise.

Through the journey, crossing rivers and climbing mountains and hills, I came to realize in one sense that being part of it was far better than the excursion we attended some years ago in kindergarten 1: “You see that big tree there? And that river?”, said the tourist guard. “I wish you people are old. We could go there and feel them.” And every time we nodded and replied “Yes, Sir” like some programmable robots and that was the end of it all.

At a point in time, we met a few farmers. Some such working on their farms and others too heading towards their farms like us. There the local dialects were forced into early English greetings: “Morning!Morning!Morning, Torgbe-and-son!”, unpolished words, recklessly merged together with no sense of guilt as you read it, and hard words that came so fast as the streak of lightning as they struck your eardrum. Hard and frigid greetings that made me believe that my people had lived all their lives with no iota of patience and love. Indeed, Africa is a hard place but I always wanted to ask dad about the haste in such greetings. “Edudzi, you should be grateful that they greeted at least. Others will see us as a scarecrow and just pass by. Carry your legs as fast as you can; it’s almost sunset.”, and that was the only response most of the time.

Chapter 4

Several minutes of trekking drew us closer to our destination. Over the veteran mahogany tree was the farm but we had to first cross the Tenu River. The Tenu River was a very large river that served the whole community of farms. I remember dad telling me one day on the farm that Tenu initially had no name and wasn’t originally large like we thought but several nearby rivers had gradually merged into it, developing it into large river, eventually earning its name Tenu which according to our people means ‘Anointed’. After all, hasn’t its significant meaning made a positive impact, saving the community from drought effects and thirst? Surrounded by vast veteran trees that kept it perpetually green and at the same time provided it with a canopy, Tenu River, as many would swear, never knew the skies. On rainy days, it came much alive and flooded nearby farms, and the owners had to bear the brunt of seeing their crops or produce soaked: the negative aspect of the story.

We eventually got to the farm. The maize and the yam had done so well. Next season was going to be cassava, pepper, and some green leafy vegetables, I supposed. We reclined in the farm hut to gather some rest. Dad told me to pluck some fresh mature maize which we roasted and ate right away. Dad never ate much and you are lucky as a child when your parents eat less because there’s always some surplus food reserved for you. So I was glad to ‘attack’ and munch the rest of the maize until my stomach was completely filled up and taunt and until I could hardly breath through my mouth.

Dad had already taken to the fresh yams. They were thick brown yams, some attacked by yam beetles but dad was glad to have quite a few good ones. But at my age, I never knew what a good yam or a bad yam was and I never disgusted those pests either because I had a friend in school who told me his father ate them with delight and that’s okay; all daddies are good.

“Edudzi! Are you still on that roasted maize?!”, dad threatened. “Get up and fetch me those two big sacs or else you’ll go home!”. I didn’t want to go home so I fetched the sacs quickly and handed them to him. I watched with a guiltless face as dad effortlessly rooted out those thick pieces. It was a nice sight. I tried to feature in, got hold of one of the pieces, and tried with all my might but this piece wouldn’t acknowledge my efforts and was stuck in there, staring at my ten-year innocent face with impunity. “Edudzi, give up on that tiny yam and I promise you you’ll miss dinner!”, dad cautioned but the reality is I was more than too tired to fight the tiny but stubborn piece again. The maize I just ate had already been dealt with and I was hungry the more. “You’ve seen your life? It’s okay! It’s okay!”, dad teased. “Just pack the pieces in the sacs and let’s keep going”.

Dad uprooted, and I loaded. Dad uprooted, and I loaded… We kept on in that manner and the two sacs were almost full. That principally meant we would be hanging up duties anytime sooner and there I remembered mum had still not arrived with the food.

Chapter 5

We were engrossed in the labor and were left point-blank about the changing weather. The sun had begun to betray and was earnestly going down. Then the first thunder came “Gbla!” and shook the entire farmland, and the clouds turning thick and scary black. Dad woke up abruptly from the trance. “Leave those yams behind and run into the hut!”, dad warned and followed. The scene was no different from a mob chase in a wild street. The thunder and lightning were the mob and dad and I were the innocent thieves. A few metres from entering the farm hut, our hope was left flat - the strong winds crushed the poor structure and yanked its roof away. We were bewildered. How could the wind be so wicked? I had developed instant goose pimples and was as scared as a squirrel. When the heavy downpour started its work, I could sense my heart hanging down my underside. “Edudzi! Let’s run home! Run home! Run home! Run home!”, dad’s voice echoed in agitation as we dashed through the storm, leaving the yams and everything we had brought to fight the storm.

I never for once saw dad run. He always walked or strode but this terrible scene had given me the chance to see him, of all people, run. And as a child, seeing the elderly doing something new, something they never gave you the green light to see, is a spectacular sight. The storm came much stronger and I could feel my body being tossed here and there by the daring wind. The slippery paths added to our woes and at a point, I slipped and fell and dad would grab me to stand and the bolting went on, but when dad fell, he knew he had to help himself to rise to the feet because he and heaven know I, Edudzi, was just some rickety straw. Fell, stood up, ran. Fell, stood up, ran. Fell, stood up, ran… and that was that and the downpour had drenched us to the bone.

Chapter 6

Miraculously, we got to the village center and the clouds had held the storms. From storm straight to drizzling, a very baffling experience. Was nature angry with us? What crime did we commit to suffer such an adversity? A few folks would peep their heads out of their huts and saw father and son looking stranded in the rain and a few yelling out their condolences but oblivious to what happened and how it happened.

“Edudzi, hope you’re all right?”

‘Yes dad but I fell on my bum and I want to cry.’

“Man doesn’t cry. You’ll be fine.”

‘All right but dad, I’m not a man…’

“Would you shut up?!”

‘Sorry dad but hope you’re also well?’

“Yes, I am, my son.” …

Such was the backchat between us as we stood in the drizzle. Dad couldn’t believe what happened and neither did I and we stared into each other’s faces with fear and disappointment. The falls made us muddy and that we had to stay in the drizzle for a while to drain off the dirt.

The Tedudu Festival is the very next day? Without those yams, how is our home going to celebrate the Tedudu Festival? Such were the questions we asked each other. It was getting late and going back to the farm to fetch those yams was quite risky; we may have to serve the night. And besides, the chief had forbidden anyone from going to their farm from 5 pm and it was getting darker here. Those pieces definitely would have to be brought home but not for now. Perhaps, the next day would do because we couldn’t abandon them like that to rot. What was the sweat for? Mum is going to be sad. Little Adjo will whimper all night and will reserve the remaining tears for the next day. I always found it strange why my little sister, Little Adjo could cry for hours over mere incidents that many would simply forget and move on. Even if a frog died, she cried. She misplaced her own fallen tooth, she cried. She could have earned a degree in mourning if only there’s one. I must say with this attitude, I was too gentle with her because she wouldn’t spare the next second crying her eyes out over any obstruction I committed and dad and mum may think I hit her and thus get me punished.

Big Kossi may be coming home from the city few hours from now to only meet our tragedy. Who will sell his yams to us on a day to the Tedudu Festival? We however decided to put the defeat behind and went home. The door was locked. The compound was quiet. Mum and little Adjo may be in. Dad knocked and the door was opened. “Ei Kossi! When did you arrive?”, dad let out and tried to force in a smile. “I came about an hour ago. I brought enough yams too.” Goodness! Before the last words dropped, dad and I flew and hugged each other in thorough bliss. The jubilation was more electrifying than our enemy storm.

Of course, Big Kossi knew we needed to be happy because he brought yams but the extreme of our joy was something he found very strange. “Where is mum then?”, I asked. “She’s going to fetch some red earth at Uncle Delanyo’s place.”, replied Big Kossi. Uncle Delanyo was mum’s younger brother, was as kind as a turtle but never had sympathy on his debtors. How could he lend them his money when they were in trouble but refused to settle him? Mr Agadzi, the palm wine tapper had received his share of those heavy blows which nearly landed the former at the mortuary. I doubt the funeral would be short of wine. I ran helter-skelter towards Uncle Delanyo place, amidst ranting my self-made festive song:

“Yam must live, hey!”

“Its sweetness, wow!”

“Yam must live, hey!”

“Its sweetness, wow!” …

I was soaked in my new track and was oblivious to whom and what I met in the alley. “Bam!”, I mistakenly ran into and fell on a matronly woman who was perhaps sending food to her husband’s house. I knew the woman and so did she. She sometimes brought firewood to mum but it’s her name I could not remember. The basket of food was chucked in thin air and the balls of kenkey and okra soup, scattered on the ground. I could smell green pepper here, chopped onions there and palm oil all over. “Oh, crabs here again?!”, I quivered and this reminded me of that morning when I sneaked into our kitchen to pick one in the okra soup. It was a fresh soup mum had prepared the preceding night. No one at home and mum gone to the market, what other freedom could Edudzi crave for? I felt the world was all mine and broke two claws to sate my sweet tooth. Nature lost my two upper front teeth some days ago and my premolars had to do the biting. Then, out of the blue, came a heavy knock on my head “wham!”, a knock that echoed in my brain and drove me crazy, and there stood mum behind me looking menacingly into my eyeballs like a warrior hen. I yelled, fled from her hands and dashed out of the kitchen. My night was absolute hell when dad got to know. From that day, I hated crabs and I was scared of crabs and I would always run away from crabs.

From the woman’s soup, I could tell those crabs came from a good market and crabs formerly my favourite, I knew I had totally killed her husband’s appetite and I felt so guilty. “Oh, sorry for the harm! Your water drums may be empty. I won’t hesitate filling them.”, I said. “Spare me this evening and tell my parents not if not, I’m finished!”. The woman looked wild and gave me a hard kick on the buttocks and told me to leave immediately. I harboured the heat in my buttocks, suppressed the hot tears, sworn to amend my rough ways and broke away back home.

Chapter 7

The Tedudu Festival served us quite well. The chief and the entire clan remained forever grateful to all and sundry that made the festive season a success. The next morning was thanksgiving and mum took Little Adjo and me to church. On thanksgiving days, both adults and children worshipped together unlike the other days. It was a cool service but the senior pianist must have gone somewhere. The substitute, a bony man in an oversized brown coat would press a key so long until the rhythm rose above the din. The next sound came when you had totally forgotten if there was any pianist. However, I was enjoying the sound but somehow, the elders couldn’t take things anymore and gently signalled the gentleman to exit and save his energy. Well, sanity took over the atmosphere and there was an altar call. I didn’t know what an altar call was but then, the pastor elaborated that those who wanted to accept sweet Jesus and turn away from their odd ways should come forward so that he, the pastor could pray for them. A few adults and some of my colleagues joined. Kpakpo, the boy who stole the piglet in the chief’s pig farm also joined. Hmm, this Kpakpo boy really had the courage. A whole pig’s baby not even mango? I was wondering where he hid it. Well, mum’s face spoke volume and I knew what would become of me if I should just lie there like a wood.

“Sweet Jesus, thanks for the Tedudu Festival. The yam was sweet but I guess you don’t eat one. Dad and mum say I’m stubborn and I don’t know what they mean about that. Please, I want mum and dad happy because they give me food. If that thing called ‘stubbornness’ is what makes them unhappy and they believe it’s in me, then sweet Jesus, please take it away from me. And sweet Jesus, they say you can hear us everywhere and anytime. They also say the church is your house but I’ve neither seen you here nor met you before and neither any of these members have. Sweet Jesus, where are you hiding? We long to see you. Edudzi longs to see you. Please, come in one of those big trucks and take us away. And don’t forget to bring plenty bread because Auntie Mansa, the baker had travelled for months and we don’t know whether she’s dead or alive. Sweet Jesus, I want to cry. I’m crying now. Listen to my prayer, Sweet Jesus. Amen.”, I sobbed and prayed naively and inwardly as I walked through the pews to receive my salvation.

#AfricanStory #NircleStories