Early Beauty Standards in Nigeria

Beauty Stories@beautystories

2 months ago

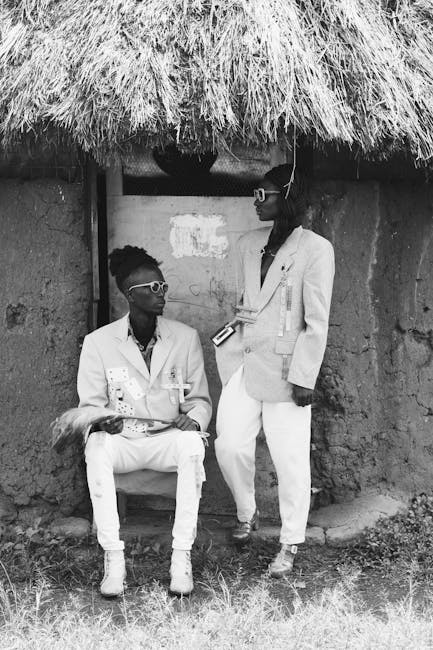

Early beauty culture in Namibia is a profound reflection of its diverse ethnic groups, environment, and social structures, long before colonial influence. It was deeply functional, spiritual, and communicative, far beyond mere ornamentation.

Here’s a breakdown of early Namibian beauty culture, organized by key themes and ethnic groups:

1. Core Principles & Materials

Beauty was not separate from survival, status, or spirituality. Materials were sourced entirely from the local environment:

· Ochres & Clays: Red, yellow, and white ochre (from iron oxide) were fundamental. They protected the skin from sun and insects, and held ritual significance.

· Animal Fats (Butter): Used as a moisturizer, base for pigments, and to create a glossy, luminous sheen on the skin—a celebrated aesthetic.

· Herbs & Plants: For scent, cleansing, and treating skin conditions.

· Shells, Bones, Ostrich Eggshells: For jewelry.

· Iron and Copper: For jewelry among metallworking groups like the Ovambo.

2. Ethnic Group Specific Practices

The San (Bushmen)

· Skin: A mixture of fat, ochre, and aromatic herbs (like buchu) was daily wear. It provided sun protection, hydration, and a distinctive terracotta color and earthy scent.

· Hair: Intricate braiding and styling, often adorned with small ornaments. Hair was a social canvas.

· Adornment: Leather headbands, necklaces, and bracelets made from ostrich eggshell beads (painstakingly made), sinew, and seeds.

The Nama and Damara (Khoisan groups)

· Skin: Similar use of animal fat and ochre. The famous Nama women's hairstyle involved many tiny, plaited locks (dreadlocks), sometimes stiffened with a mixture of fat, ochre, and herbs.

· Clothing: The "Victorian" dress (* rob) adopted later from missionaries was transformed into a vibrant cultural statement with bold colors, multiple petticoats, and distinctive hats—a fusion that became a new beauty standard.

· Jewelry: Extensive use of beads (later glass trade beads) in geometric patterns.

The Ovambo, Herero, and Himba

· The Himba: Perhaps the most iconic. The otjize paste (a blend of butterfat, ochre, and aromatic resin from the omuzumba shrub) is central. It beautifies, cleanses, protects from harsh desert sun and insects, and symbolizes the earth's red color and blood (life). Hair is also styled with otjize and extensions (ezembe), with elaborate hairstyles indicating age, marital status, and social rank.

· The Herero: Pre-colonial hairstyles were complex and symbolic. The later adoption of the Victorian-style dress evolved into the formal, cow-horn shaped Otjikaiva headdress, a powerful symbol of identity and resilience against colonialism.

· The Ovambo: Practiced scarification (ilenga) on the torso and face for beauty, rite of passage, and status. Elaborate hairstyles and jewelry made from iron, copper, and beads were important.

The Kavango and Caprivians

· Hair: Intricate plaits and styles.

· Body Modification: Tooth filing (chiseling teeth to points) for beauty was practiced.

· Jewelry: Beadwork and ornaments made from local materials.

3. Key Cultural Functions of Beauty

· Rites of Passage: Hairstyles and adornments changed dramatically at puberty, marriage, and childbirth.

· Social Status: The complexity of hairstyles, the amount and type of jewelry, and the quality of otjize (for Himba) indicated wealth, marital availability, and rank.

· Spiritual Protection: Many pigments and practices were believed to ward off evil spirits or connect with ancestors. Otjize, for instance, has a spiritual dimension.

· Ethnic Identity: Styles were immediate identifiers of one's people and homeland.

4. Colonial Impact & Syncretism

The arrival of German and South African colonizers brought new materials (glass beads, fabrics) and imposed Western beauty standards, often denigrating indigenous practices.

· Syncretism: Groups like the Herero and Nama subverted imposed Victorian clothing, transforming it into a celebrated, hyper-stylized ethnic uniform.

· Resistance: The conscious continuation of practices like Himba otjize or Herero headdresses became (and remains) an act of cultural preservation and resistance.

Conclusion

Early beauty culture in Namibia was a holistic system of environmental adaptation, social communication, and spiritual belief. It was inherently sustainable and deeply symbolic. Today, while modern influences are strong, there is a powerful revival and pride in these traditions, with many communities continuing or adapting these ancient practices as a core part of their identity in the modern nation. The iconic imagery of Himba women, Herero ceremonial dress, and Nama-style dresses are living testaments to this rich heritage.

2 months ago

2 months ago

2 months ago

2 months ago

2 months ago